Identities — Itamar Freitas’s review (UFS), on the book “Negras(Os) da Guiné e de Angola: nações africanas, vivências e sociabilidades em Sergipe (1720–1835)”, by Joceneide Cunha dos Santos

Abstract: Negras(Os) da Guiné e de Angola: nações africanas, vivências e sociabilidades em Sergipe (1720 – 1835), written by Joceneide Cunha dos Santos, investigates the identities of African men and women, resident in Sergipe, in the 17th and 19th centuries . The author defends the thesis that the processes of identification of these people depended, among other factors, on the rites of marriage, baptism, experience in brotherhoods and burial.

Keywords: Black people, Black women, Africans, Identities.

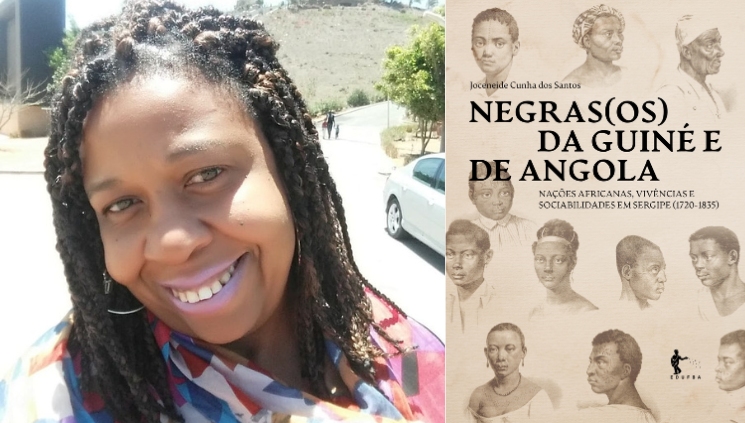

Negras(Os) da Guiné e de Angola: nações africanas, vivências e sociabilidades em Sergipe (1720 – 1835) was written by Joceneide Cunha dos Santos and published by Edufba, in 2021. The book communicates competing objectives. The first is to demonstrate markers of ethnic identity among Africans who inhabited the territory of Sergipe, between 1720 and 1835, a period over which the available notary sources make this examination possible. The second is to capture experiences of “lives and sociability” of Africans on rural properties (p.48, 28). The third is to “analyze the experience of Africans according to gender” (p.47).

Joceneide Cunha dos Santos is a professor at the State University of Bahia, PhD and master in History, with a career marked by work with black and slave populations, in the regions of Sergipe and Bahia. Since her Scientific Initiation days, the author has become accustomed to examining registry archives from the 18th and 19th centuries, doing what the historian Josué dos Passos Subrinho, her first advisor, liked to call the routine of “counting slaves”. From the socioeconomic approach, the author migrated research on the family experience and today engages with the gender perspective.

In the book, these career tones still appear, as we will see, in the distribution of the five chapters, communicating part of his doctoral thesis, defended at UFBA, under the guidance of Carlos Eugênio Virgínia Soares. In the first, the author builds “a profile of the economic activities of the residents of Vilas Sergipanas (1720–1835)”, as stated in her subtitle. It is a long (79p.) piece of socio-economic contextualization in which it argues that the economic growth of the captaincy (and, later, province) of Sergipe triggered a parallel demographic growth, including the increase in the African population. The seven villages are described as diverse in economic activity, resulting in populations more focused on sugarcane, cassava and tobacco agriculture, for example (São Cristóvão, Santa Luzia and Santo Amaro), agriculture (Itabaiana and Lagarto) and livestock (Vila Nova and Propriá).

The second chapter interrogates baptism books to identify the meaning of this sacrament. Paraphrasing Koster, the author states that “newly arrived Africans wanted to be baptized to become like those who were already in American lands.” (p.141). Following part of this premise, the author notes the construction of “protection and solidarity” networks through “cronyism”, which varied from parish to parish. Given the rarefied presence of enslaved people in certain places, the author identifies interactions that include freed and free people. Another goal of the chapter is to inventory ethnic markers, metaphorized in the expression “nation”. From the data collected, mainly in the “agropastoral” villages, it was possible to notice nagôs circulating close to the main church and jejes and angolas circulating in the chapel of Rosário dos Homens Pretos.

In the third chapter, the author outlines a profile of the “slave population” based on wills and inventories produced in Santa Luzia, Itabaiana and Santo Amaro. There begins the systematic dissemination of the origin of this population: Central-Eastern Africa — Angolas, Benguela, Gangela (24%), West Africa — Arda (10.6%), East Africa — Mozambique (4.54%) and Brazil — Creoles and mestizos (46.98%). As the author herself states, these data serve as estimates because the number of people identified is tiny (p.83). Considering the occupations linked to the universe of sugar cane, mechanical, domestic, transport and rural arts, among others, the author concludes that the Angolan majority “had greater access to trade specializations” and greater “chances of forming a community and (re)construct identities [since] they found people from their nation more easily in their slave quarters or in neighboring ones”, enabling the “construction of solidarity networks” (compadrio and brotherhoods) (p.237).

The fourth chapter is reserved for identifying the “nations” of the 19th century. The author informs that the sources for the period 1821 – 1835 indicate an increase in the number of identities, with the majority, quantitatively, being those identified as Angolan and Jeje. This expansion occurs in relation to the detail of identification that goes beyond the generic (“African”) level, for example, to specify “Angola” and, within this, “Monjolo”. I warn that this taxonomy receives a fourth and

most generic level, built under spatial demarcations of the African continent (central-western, eastern, western). The same occurs with the “African” / “Congo” / “Bacongo” taxonomy. The older and more numerous the slaves under the same property and economic function, the greater the possibility of linguistic interaction and/or formation of networks (through baptism, marriages, brotherhoods). In the same chapter, the author declares that the age group of 26/40 years was dominant among Africans, with a greater balance between those born in Brazil, young people and children. In terms of occupation, finally, there was an increase in the number of enslaved people who worked on the plantations (alambique maker, boilermaker, purger, sugar master and cashier), although the urban trades were the majority (bricklayer, sawyer, carpenter, among others).

In the fifth and final chapter, the author details the role of brotherhoods in building sociability and protection networks for enslaved and freed people, mainly in São Cristóvão and Santo Amaro.

The creation of these networks and the consequent recreation and creation of identifications is carried out, above all, in the participation of enslaved and freed people as musicians, players of taieira and cacumbi, in the coronation (sometimes clandestine) of the kings of Congo. Brotherhoods, in addition to festivities, are effective solidarity schemes, when they enable communion and confession, lend funeral coffins, offer prayers, provide spaces for burial among equals.

Taieiras de Laranjeiras – SE | Image: Canal Carlos Maguary/Youtube

The contributions of the work, however, differ from the sparse typographical revision errors and the presence of demarcators of a genre extinct with the publication of the book: “thesis”. Other problems, however, deserve greater attention. The first teles has to do with the hypothesis. I saw no reason to announce a hypothesis centered on the presumed statement that Sílvio Romero and João Ribeiro were talking about Sergipe, when they dealt with the Bantu majority in Brazil. The search for diacritical markers, considering different dimensions of the experience of Africans, as done in this book, is much richer and socially relevant.

The second observation is related to information architecture. I think the book would survive without the first chapter. It is likely that the author has succumbed to the almost canonical principle that symbolic phenomena (and African identities fall into this type) are understandable only with knowledge of their economic (or economic-social) basis. But the context (the text that guides the understanding of another text in the form of efficient cause or necessary cause) could be constructed parallel to the description of the phenomena in chapters two, three and four.

Thirdly, the author leaves the reader to discover the taxonomy on identification. Only after 200 pages does he discover the strategy of carelessly presenting the taxonomy variables for the declaration of identity or “nations”.

Lastly, I think that the rarity of the discussion on gender does not justify its transformation into a core objective, since the mentions are limited to specific hypotheses about female empowerment through negotiation with landowners or free men.

As I almost always review with novices in mind, I now present some virtues of the work (perhaps not so virtuous in the eyes of specialists in the history of Africans in Brazil. The author searches for “identification” and “identity” of the enslaved. She describes the polyphony of voices, teaching that the comparison of speeches, considering the owner of the voice, is a basic task: the voice of the enslaved, the translator of the enslaved, the owner of the enslaved, the known free/freed person of the enslaved, the mediator of enslavement, the priest . Who has authority over the discourse of identity? It is the historian, using intricate contextualization operations. Here and there, she is obliged to examine phenomena in certain regions of the African continent or the captaincy/province of Bahia to identify oppositions and probable (re)identifications of the enslaved people who inhabit Sergipe.

The allegories at the beginning of the chapter (from 2 to 6) should be praised as clues for those who intend to use the book as a source for the construction of teaching material. Some short narratives have identified characters, others do not. The objective, to be imitated, is to produce a reality effect with numbers, adjectives and nouns systematically crossed to demonstrate the slave woman’s achievements.

The use of sources is highlighted, especially for those new to research. I will give an example with baptisms. The author listed, classified, quantified and tried, thoughtfully on variables that included color or nationality (African Angolans, Africans, Angolans, Brazilians, Cabindas, Congo, Costa da Mina, Creoles, da Costa, Haussá, Jeje, mestizos, Mina, Mozambique , nagô and tapa), legal status (slave, freedman), age group (

boys, men), gender (male/female), and crossed these variables, for example, to establish a typology of godfathers and godmothers (slaves, free or freed/married or not married to each other).

From this processing, he concluded what he considered to be safe and also left open questions. Here are some examples: she found enslaved people married to the same enslaver and asked: was there negotiation between master/slave? Would the slave be a leader? She found sponsorship inside a slave quarters: would kinship mean ritual and/or alliance, would it mean the reconstitution or creation of new identities in process? She found hundreds of records of the generic word “African”: Was the parish priest omitting the “nation” to protect the enslaver from possible punishment by the authorities for illegal trafficking? She found a slave baptized under an African toponymy: could this be a sign of origin from the Niger River?

After this inventory of benefits and noting the drawbacks mentioned about the dialogue with João Ribeiro and Silvio Romero, as well as the discussion on gender, we can only add that the book fully fulfills the announced objectives, as can be seen after an accurate examination of its final considerations. There, the questions are revisited and the answers presented succinctly, that is, the denominations of Africans were generic and varied in intensity between the 18th and 19th centuries and their respective identities were constructed in different situations of coexistence and rites of passage, which included marriage, baptism, engagement in brotherhoods and burial. It should be read, mainly, by Sergipe teachers who created a curricular component for high school specialized in the history of Africans and Afro-Brazilians in Sergipe territory.

Summary of Negras(Os) da Guiné e de Angola: nações africanas, vivências e sociabilidades em Sergipe (1720 – 1835)

Apresentação | Josué Modesto dos Passos Subrinho

Prefácio | Carlos Eugênio Líbano Soares

- Introdução

- 1. Lavradores e criadores: um perfil das atividades econômicas dos moradores das vilas sergipanas (1720 – 1835)

- 2. A entrada de homens e mulheres de nações africanas nas terras sergipanas e no mundo cristão

- 3. Construindo uma torre de Babel africana nos setecentos: nações e trabalho de homens e mulheres africanas

- 4. O mosaico das nações nos oitocentos: demografia, trabalho e sociabilidades

- 5. Os homens e mulheres africanos nas Irmandades do Rosário dos Homens Pretos nas terras sergipanas

- Considerações finais

- Referências

Reviewer

Itamar Freitas is PhD in Históru (UFRGS) and in Education (PUC-SP), professor at the Department of Education and the Professional Master’s Degree in History at Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS) and the Postgraduate Program in African Studies, Indigenous Peoples and Cultures Negras from the Universidade do Estado da Bahia (Uneb) and editor of the blog Resenha Crítica. He published, among other works, Uma introdução ao método histórico (2021) e “Objetividade histórica no Manual de Teoria da História de Roberto Piragibe da Fonseca” (1903-1986) (2021). ID LATTES: http://lattes.cnpq.br/5606084251637102; ID ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0605-7214; Email: itamarfreitasufs@gmail.com.

Itamar Freitas is PhD in Históru (UFRGS) and in Education (PUC-SP), professor at the Department of Education and the Professional Master’s Degree in History at Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS) and the Postgraduate Program in African Studies, Indigenous Peoples and Cultures Negras from the Universidade do Estado da Bahia (Uneb) and editor of the blog Resenha Crítica. He published, among other works, Uma introdução ao método histórico (2021) e “Objetividade histórica no Manual de Teoria da História de Roberto Piragibe da Fonseca” (1903-1986) (2021). ID LATTES: http://lattes.cnpq.br/5606084251637102; ID ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0605-7214; Email: itamarfreitasufs@gmail.com.

To cite this review

SANTOS, Joceneide Cunha dos. Negras(os) da Guiné e de Angola: nações africanas, vivências e sociabilidades em Sergipe (1720 – 1835). Salvador: Editora da UFBA, 2021. Review by: FREITAS, Itamar. Identities. Crítica Historiográfica. Natal, v.3, n.12, Jul./Aug., 2023. Available at <https://www.criticahistoriografica.com.br/en/identities-itamar-freitass-review-ufs-on-the-book-negrasos-da-guine-e-de-angola-nacoes-africanas-vivencias-e-sociabilidades-em-sergipe-1720-1835-by-joceneide-cunha-do/>

© – Authors who publish in Historiographical Criticism agree to the distribution, remixing, adaptation and creation based on their texts, even for commercial purposes, as long as due credit for the original creations is guaranteed. (CC BY-SA).